The Man from International Rescue

Martin Chandler |

I was six years old in 1966, and like most small boys I was only interested in three things that summer. There was the FIFA World Cup, held in England for the first time, which we won and, to put some icing on the cake, did so by beating West Germany. To make things even better the tournament took place in the summer, and ran alongside a tour by the best cricket team in the world, West Indies, who were led by a man with the reputation of being the most exciting cricketer who had ever lived, Garry Sobers. If that sporting feast was not enough then on those rare occasions when there was no cricket or football on the television we had Gerry Anderson’s Thunderbirds to watch. For the vast majority of people there is absolutely no connection between cricket and Anderson’s marionettes, but I found a startling link that has remained at the forefront of my mind to this day.

Although my development into a cricket tragic was by definition at an embryonic stage I had heard of John Edrich, probably because he had scored his triple century against New Zealand the previous summer, although I have no recollection of seeing any of the innings nor, consciously at least, of having seen Edrich by then. He didn’t play in the first four Tests of that 1966 summer, and only came back as part of the wholesale changes made by the selectors for the final Test at the Oval. The match was one of the more remarkable in Test history, England’s last three wickets adding 361 to set up a consolation innings victory, but I don’t really recall that. My abiding memory of the match was watching John Edrich walk in at first drop. It looked for all the world as if it was one of Tracy brothers, the pilots of the Thunderbirds, going in to bat. The combination of the bushy eyebrows, the dimpled chin and the hairstyle were what did it, although the slightly grainy quality of our old black and white Radio Rentals television set, which afforded the possibility of believing that there were some strings there, completed an illusion I have never forgotten.

Wisden tells me that Edrich scored 35 that day, although I have no memory of that, but I do recall learning that he was a cousin of former Test star Bill Edrich, who I knew something of. I assumed, being just six don’t forget, that Edrich must be a common name, but I found out that in fact it wasn’t, and that the two Edriches who had played for my beloved Lancashire, Geoff and Eric, were members of the same family, as indeed was another one, Brian, who played for Kent and then Glamorgan. The four senior men were all brothers, and John their cousin. As my cousins were all around my own age I struggled for some time with the concept of the age difference, but eventually grasped it. There were fifteen years between the fathers of the two families, the eldest and youngest of nine sons (out of a total of thirteen children) of the patriarch, Harry Edrich, a man of Norfolk.

John was a decent left handed batsman, but as an opener he had a tendency to be effective rather than entertaining, and it was a few years before I had acquired a sufficiently strong grasp of the subtleties of Test cricket to enable me to appreciate his value. Once I did he quickly became one of my favourite players, and what I admired most was his courage, something which I found out was most definitely a family trait.

Bill’s story was the most inspiring. He was a bomber pilot during World War Two, and survived despite well over three years active service. Not surprisingly he picked up a Distinguished Flying Cross along the way, and took all the bravery he showed on the cricket field into the air. Nothing fazed him. In the 1946/47 Ashes series, whilst fielding at short leg, a ferocious shot from Sid Barnes hit the inside of his knee, causing substantial swelling. As would be expected he stayed on the field, but could not weight-bear on the injured leg and was persuaded after an over to retire to the dressing room. Later that day Bill Voce pulled up, and England were a bowler short. Whilst always a frontline batsman in those days Edrich was also a pace bowler, genuinely quick if lacking in accuracy. Next morning he was still lame, but came straight on to bowl, and with three wickets helped wrap up the Australian innings before top scoring for England.

The bravery of the senior cricketing Edrich also signalled the start of Frank Tyson’s advance. In July 1954 The Typhoon made his first appearance at Lord’s in a First Class match, against Middlesex. The England selectors were all there and Tyson’s duel with Bill was the catalyst for his name finding its way on to the list of those invited to tour Australia that winter. The Lord’s wicket was a quick one, and the famous old ridge made Tyson’s deliveries fly. When, towards the end of the second day, Bill arrived at the crease the light was beginning to fade. In good batting conditions Tyson was a terrifying proposition to most, and these conditions were anything but good, but Bill relished a fight. The first ball he received was a short one that he sought to hook, but succeeded only in top edging into his face. The result was a great deal of blood on the wicket, a broken cheekbone, and even Bill needed to leave the ground for hospital treatment. He was back next morning with his face disfigured by swelling and swathed in bandages. Teammates and umpires alike begged him not to bat again, but if he was listening he certainly didn’t heed their pleas. Tyson greeted him with another bouncer, and again he tried and failed to hook, on this occasion the ball hitting him over the heart. Bill was out for 20, so it was not a major innings, but he saw off Tyson’s opening burst.

In some ways Geoff’s story was even more inspirational. He was taken prisoner by the Japanese in 1942 and spent more than three years in captivity. He weighed just six stone when he was finally liberated. When he got back to England he discovered that his wife, who had been in receipt of a widow’s pension for some time, had rebuilt her life in the belief that he had been killed in action. Happily the couple managed to sort out that nightmare scenario, and Geoff was able to get a contract with Lancashire, who he served with distinction for more than a decade. A Test cap eluded him, but he must have come close to selection, particularly in 1951 against South Africa. In Lancashire’s game against the tourists he got to 60 before being forced to retire hurt after being struck on the head by a bouncer from Cuan McCarthy. Twenty minutes and three wickets later a patched up Geoff was back. He was eventually out for 121 and his side enjoyed the better of a draw.

Eric, the eldest, did not join up, I believe as he was in a reserved occupation. After the war he went to Lancashire with Geoff, and his presence there undoubtedly helped his younger brother get over the psychological legacy of his years in captivity, and his difficult domestic circumstances. Eric was not an outstanding cricketer, but was a competent wicketkeeper batsman. He stayed at Old Trafford only three years, but as one of his two centuries came in a Roses match, he left with the best wishes of all the county’s supporters. As for Brian he was the youngest, and just 17 when war was declared. Like Bill he became an RAF pilot although as far as I can see he flew transport planes in India rather than in combat zones. His First Class career lasted ten seasons, and he was a useful all-rounder, but nothing like as good a player as Bill or Geoff.

At least one Edrich played in every First Class season between 1934 and 1978, although to all intents and purposes John flew the flag alone from 1959 onwards. His entry to the professional game was delayed by National Service, and his early games for Combined Services were disappointing, but at 21 he was selected to make his debut for Surrey. The county had just wrapped up their seventh consecutive Championship, and this was the last game of the season, at home at Kennington Oval, against mid-table Worcestershire. It was skipper Peter May who dropped out to accomodate John, but apart from that Surrey were at full strength. The second day was washed out, and John did not get to the crease in Surrey’s truncated first innings, so he had to wait until the second innings, when his side were chasing 175 for victory, before he batted for his county. He must have wondered what was going on, as the strongest side ever to grace the county game were bundled out for just 57, but it was no fault of the debutant who, after making his entrance at 7-3, was the last man standing, unbeaten on 24 at the end.

The following season John came in for Surrey’s second match of the season, as Mickey Stewart’s opening partner, and he scored a century in the first innings and then, just to check note had been taken, added another at the second attempt and five more before the end of the season. There was real expectation that he might make the touring party to the Caribbean that winter, although in the end the selectors conservatism won the day and he missed out. The bigger surprise was that thereafter, despite performing consistently for Surrey, he had to wait until 1963 and England’s travails against Wes Hall and Charlie Griffith before he was finally picked for England. He performed reasonably well in the first Test, before failing in the second and being dropped. He was back for the fifth, and like on debut made a start in both innings. He got 25 in the first innings and probably should have retired hurt when Griffith struck him on the elbow. When he was dismissed the joint was so swollen and painful that he had to go to hospital for treatment. It didn’t, of course, prevent him from taking his place at the top of the order in the second innings.

By the end of his career John had scored all but 40,000 First Class runs at 45 and, with 103, was one of the exclusive group to have scored a century of centuries. He played for England 77 times and averaged more than 43 at Test level. Those figures put him just short of the highest class, his major weakness being a tendency, in common with many left handers, to follow the ball slanted across him and provide the slips with catching practice. As he got older his shot selection became more judicious, but it was a fault he never fully eradicated. In addition he tended not to move his feet a great deal, and as a result he never looked particularly comfortable against good spin bowling. But there were plenty of strengths in addition to the endless courage. He was particularly severe on anything pitching around his leg stump. He was noted also for a powerful square cut, and a cover drive that was up there with the best. He did not often venture on to the front foot to drive, but did possess a lofted on drive that brought him many sixes. In 1965 there were as many as 49, a season’s tally that at that time had been exceeded only by Somerset’s legendary big-hitting all-rounder, Arthur Wellard.

There were five sixes in that unbeaten 310 against New Zealand, and 52 fours as well, but in the very next Test of that summer he ducked into a delivery from Peter Pollock that was not the bouncer he expected, and suffered a sickening blow to the head. It was his first and, as history turned out, only Test against South Africa. The injury meant that of the 26 Tests England had played since his debut he had been in the final eleven for just 10 of them. He then seemed to have broken through when he played in all of the 1965/66 Ashes series with conspicuous success, but then the softer pitches in New Zealand did not suit him and what should have been a relatively relaxing three Test series turned into something of a nightmare for him, hence it taking him until that final Test of the 1966 series to force his way back into the side. The following season, 1967, John made it 12 out of 32 by losing his place after failing twice against the none too strong Indian visitors, but he was back for the 1967/68 series in the Caribbean and finally he had arrived. He went on to appear in all of England’s Tests between then and the end of the 1972 Ashes series when, at 35, it seemed his career was over.

In 1970/71 Ray Illingworth’s side regained the Ashes and John, who averaged 72 with two centuries and four fifties, was the immoveable object around which the success was constructed. He failed again in New Zealand afterwards, but neither that nor a disappointing summer against India and Pakistan led anyone to suggest his place was in jeopardy. In 1972 Illingworth’s aging side were dubbed Dad’s Army, and though John made plenty of starts, he didn’t get past 49 in the series, and having declared himself unavailable for the winter’s trip to India and Pakistan no eyebrows were raised when he failed to gain a place in the Test team in 1973, and was not taken to the Caribbean in 1973/74.

John had long declared a desire to tour Australia for a third time in 1974/75, but it seemed unlikely at the beginning of 1974 that the 37 year old would be making the trip. What helped him was the paucity of Test class left handers in England. India, who had beaten England in 1971 and 1972/73, were due in the first half of the summer, and there was a general feeling that a left hander was needed at the top of the order. The selectors chose not to disturb the opening pair of Geoffrey Boycott and Dennis Amiss, but slotted John in at number three. He was a model of consistency all summer, and if there was ever any doubt about his being selected for Australia that evaporated when Boycott declared himself unavailable to tour, thus beginning his self-imposed exile that continued until 1977.

As all students of the era know Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson destroyed England in 1974/75, and with one exception none of the specialist batsmen selected by England enhanced his reputation. That exception was John, who fought as hard as ever and, after Mike Denness stood down for the fourth Test, captained England for the only time in his career. In the first innings he scored exactly 50 to hold the top order together before Alan Knott did the same for the tail. Then in the second innings he played the innings that defined him. England could not win the match, but would emerge with a draw if they could bat out the final day. John came in at 70-2, and immediately left again, a vicious lifter from Lillee cracking two ribs. Wickets fell steadily until at 156 the sixth fell, Alan Knott, and the lower order was exposed. In the face of inevitable defeat perhaps only Douglas Jardine would have done what Edrich then did, and come back out to face the rampant Australians again. He rolled his eyes skywards two runs later as Tony Greig had a rush of blood to the head and was stumped by yards. But then John batted for another two and a half hours, shepherding Derek Underwood, Bob Willis and finally Geoff Arnold in a desperate rearguard action before, with just a few minutes to go, Arnold succumbed. Jim Laker wrote later As long as this Test is remembered, and however superbly Australia bowled, the courage of John Edrich will stand out like a beacon. Sir Donald Bradman once wrote about the qualities a batsman needed and, referring to courage, said nobody in my experience possessed a fuller quota than John Edrich.

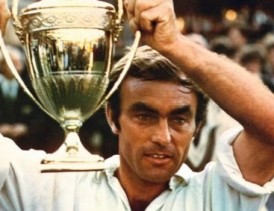

A few months later and Australia were in England for a return encounter. They carried on as before in the first Test, winning by an innings. England’s first effort was a sorry 101 all out. John top scored with 34, the only specialist batsmen to get into double figures. The debacle was the end of Denness’ time as captain. It didn’t initially seem that Greig’s time at the helm would be any different as England lost four quick wickets at the start of the second Test at Lord’s, including John’s, but then the inspired selection of David Steele came off, and he, Greig and Knott restored some pride before, in England’s second innings, John batted for seven hours for 175. It proved not to be a matchwinning effort, but did enable England to draw the game from a position of strength, and the 38 year old scored 62 and 35 at Headingley, and 12 and 96 at the Oval to enable them to do that twice more. John was not involved two years later when Mike Brearley’s side regained the Ashes, but he was largely responsible for sowing the seeds of self-belief that brought victory to Brearley’s side.

The following year, 1976, saw Clive Lloyd bring his first battery of pace bowlers to England, and the selectors turned to experience again. John scored 37 in the first innings of the first Test, adding 98 with Steele. Second time round England were in a tricky position on the last day until an unbroken stand of 101 in just over three hours between John and Brian Close, six years his senior, persuaded Clive Lloyd to settle for the draw. Injury caused John to miss the second Test, but he was back for the notorious Old Trafford match. On the evening of the third day England began their second innings needing either 552 to win or to bat out more than 13 hours for the draw. Wisden described what followed as ….disquieting cricket as Edrich and Close grimly defended their wickets and themselves against fast bowling that was frequently too wild and too hostile to be acceptable. A few years later Bob Willis described what he saw as ….the most sustained barrage of intimidation I have seen.

Immediately after the defeat Greig was fulsome in his praise for John, declaring that he was still our best opener, but it was to prove John’s final Test. Any professional sportsman is, of course, a long time retired, but judging by one comment he made after Old Trafford John would not have been too sorry to bid the international game farewell; It’s a challenge, but I can’t say I enjoy it. I am a target man, that’s all. It’s not like in a game of football where if someone kicks you, you can kick them back. You’ve just got to stand there and take it. There can be no doubt John did take “it”, and indeed everything that was thrown at him for more than two decades, and he deserved a long, peaceful and prosperous retirement more than most.

The following year, 1977, John received the MBE for services to cricket, and 1978 was his final season with Surrey. In 1981, following the tragic death in the West Indies of former teammate Kenny Barrington, he stepped into Kenny’s shoes as one of England’s selectors under the Chairmanship of former Surrey colleague Alec Bedser. He thus presided over and must take some credit for that most riveting of Ashes series, but when May took over from Bedser in 1982 John chose not to stay with the panel and English cricket saw little of him until he was appointed the Test side’s batting coach in 1995.

There has also been one last fight for John Edrich, this time for his life. In 2000 he was diagnosed with a rare form of leukaemia and told he had around seven years to live. By 2005 he felt constantly exhausted and thought his time was up. That he is still with us eight years later, and enjoying a much improved quality of life, is said to be due to treatment with injections of mistletoe extract. Scientific opinion remains mixed as to the merits of the treatment, so perhaps the answer is just the traditional Edrich one of getting his head down and presenting the full face of a straight bat at adversity.

A wonderful article, beautifully written. I enjoyed it immensely, not least due to being a contemporary of the author.

Comment by wpdavid | 12:00am BST 16 May 2013

I think that we need a John Edrich video to complement the excellent essay. And so here we have him coasting to 175 runs (Lords, 1975), and reducing Dennis Lillee to a shortened run-up in the process;

[url=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3kWQ2rxQ9Ow]John Edrich 175 vs Australia 2nd test 1975 – YouTube[/url]

Comment by watson | 12:00am BST 16 May 2013

Fine article sibling – hadn’t thought about the Thunderbirds similarity, a dead ringer for Virgil

Comment by David Chandler | 12:00am BST 16 May 2013

Not enough Thunderbirds references. Otherwise very good.

Comment by sledger | 12:00am BST 16 May 2013